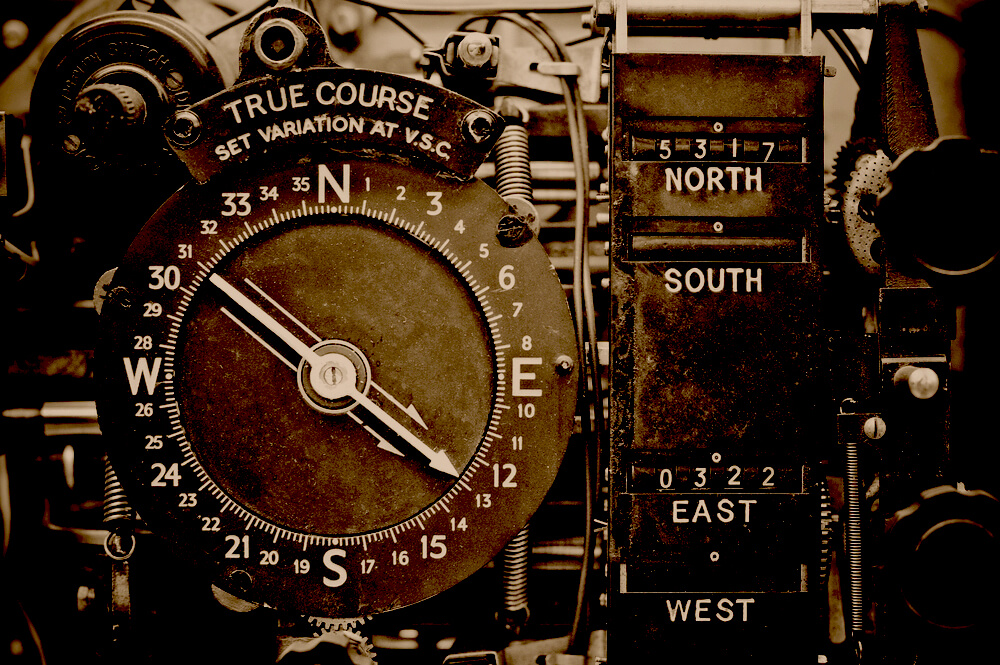

From the time we were small children, the purpose and value of a compass has been quite clear: Holding the instrument provides us with the knowledge of which direction is true north, and in turn, we can then determine the right direction to begin our trek to our desired destination.

The equally familiar moral compass allows us to immediately reorient ourselves to which is the right path in times of choice, or when confronted with an ethical dilemma involving two or more good (or, two or more bad) options. In each case, the idea of knowing the best direction for ourselves and those other roads we should avoid is fundamentally important to our ability to advance; to do right, and to be successful. But having the knowledge of which is the right path to take is only part of the solution. For whether we are on a hike across rugged terrain, or confronted with a situation in which our decision will have a lasting effect upon us and perhaps others, requires an understanding of what the ethical “True North”–or the morally correct path–is and where it may lead us to.

As an example, if we find ourselves on a journey north, but we can see that there are very real dangers ahead in the form of cliffs, raging rivers or predatory animals—we understand that we must alter our course long enough and even if it includes moving directly away from our goal so as to avoid those hazards until we can resume a more expedient, safe and direct route to our chosen location.

This can be much more difficult when we rely upon our moral compass, even if we know well the choice we should make is clear. Again, sometimes values that conflict under unique circumstances will cause us to hesitate—even question our normally solid thought-processes. Many fine people have been confronted by a personal, professional, financial, spiritual or other challenge with two or more choices only to find themselves delaying their decision as they employ some form of rationalization or justification that might resolve their uneasy feelings of making anything other than the appropriate choice. Again, these are often value conflicts, not necessarily amoral behavior.

Our values actually evolve. So much so, that they eventually provide each of us with a core of those things most important to us: Our principles. It is within these principles, that smaller, more specific set of beliefs and convictions that are most important to us that we deem as absolute or non-negotiable, from where our ethics will be illustrated through our actions. Of course, for any principle to evolve within any of us we must be challenged, often frequently, and in countless forms and versions for that core value to become stronger. And above all, we must be willing to remain steadfast to that principle, so that it may support our path in living a disciplined lifestyle and life.

However, if we routinely see one value give way too easily to another in our daily lives, then our values summarily become increasingly vulnerable to compromise, and ultimately a trend of ‘unethical behavior’. It is only through ever-increasingly complex and more sophisticated demands presented to us can we find the opportunity to grow into our beliefs structure. Or, consider this notion:

Principles that go unchallenged are merely preferences

Leaders, and the learning organizations they serve know well that True North isn’t found in the bottom line of a P&L sheet, and it isn’t captured on a plaque in the company lobby or within an annual report. But these can be reaffirmations of successfully living principled lives and performances of ethical conduct that in turn perpetuates the unrelenting power of the culture among the group, its interactions and methods, and the accountability it actively demonstrates.

As leaders, we cannot afford to influence our followers with values systems incapable of withstanding challenge or unworthy of retaining. Leaders must pursue higher standards demonstrably, consistently, and with a purpose that can be articulated. Indeed, the ‘why’ is every bit as important as the ‘what’ or ‘how’. Just as importantly, we as leaders must define our organizational cultures in a manner that preserves the expectation for others to provide their own examples of conduct, behavior, and performance to a higher standard.

This article was originally published at http://www.careersingovernment.com