In the Fall of 2003, I happened upon a book about one of my favorite subjects—baseball—and by the time I had completed reading Moneyball, I had found a way to pierce through some of the most daunting challenges facing leaders of organizations: How to find talented personnel when the organization is much less financially-resourced than its competitors.

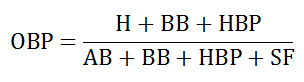

In Moneyball, the General Manager of Major League Baseball’s Oakland Athletics, Billy Beane, learned how to rely on a very simple statistic—the frequency of a player getting on base—to determine what players he could afford to sign and still maintain a playoff-contending team. The long-standing traditions of player evaluation fell by the wayside as Beane led a redirection of how his organization through metrics that worked at every level of his industry. That formula is:

It would change the game. And that interested me.

By the end of the 2003 calendar year, I was facing not one, not two, but three vacant police officer positions in an agency of just 25 sworn. Retention rates hovered around 19 months. We were going through all of the effort of recruiting and training someone to retain them for less than two years. A faster recruitment and hiring process seemed to only prepare the newest of our officers for a career elsewhere sooner. Most perplexing was that morale among employees was reported as high.

These vacancies came about because the organization at the time had a salary structure that was regularly 15-25% below market for police officers in Southern California. Many of our best were lured away to city and county law enforcement agencies blessed with much greater compensation packages.

Growing frustrated that we were (a) perpetuating our own future struggles by continuing to pour energy into (b) recruiting superior candidates through an accelerated hiring process, I had to find a new way to find qualified police professionals and a much more accurate selection criteria for officers who would find our brand of campus/community-oriented policing worth staying for.

Seeking any answers I could find, I spent several additional hours reviewing files of employees who had been employed at my organization anytime in the previous five years. What I found among the group who had been with us for three years running or more was this: The grade point averages of all high school and college coursework in English (Language Arts), History and Physical Education were demonstrably higher than that of their counterparts who had excelled at the police academy, completed our training program, and eventually continued their careers elsewhere.

The officers who had stayed longer had GPA’s that supported why they wrote effective and accurate reports (Language Arts), and why they related chronological events with detail in those reports (History). Additionally, their ability to avoid injury and illness and remain in a full-capacity to work reflected a personal commitment to care for themselves (Physical Education/Fitness). Regardless of the number of years/semesters of courses in these three categories they took, the grade point average demonstrated a consistent rate of higher retention, higher performance ratings by their supervisors, lower rates of absence and injury-on-duty, and interestingly, a dramatically-low rate of any form of complaints from the public. My new “Performance Excellence Index” became this:

The recruitment process was redesigned with the help of our Human Resources department, who became immediately intrigued by our theory. An early writing exercise helped us assess a basic communications capability and the background checks featured the GPA data prominently for managers to consider alongside other testing elements. With this new discovery, I immediately prepared myself for the interviews of candidates. Applicants recommended for background investigations were processed as usual, but when it came time to select individuals to hire, the deciding factor would be the GPA score. Almost overnight, the change was remarkable.

That initial group hired in the spring of 2004 lasted an average of 7 ½ years. Two of the people hired that year have since promoted twice and continue to serve with distinction as supervisors. Since that time, the retention rate of employees is now around 9 years—an extraordinary return on the investment of recruiting. And while the salary and compensation remain below market averages, the emphasis on the GPA as an indicator also assures us that the individual appreciates an environment of learning, and thus, performing as a police officer upon a college campus reinforces this value to them.

Since then, I have employed the same criteria in each organization I have had the privilege of leading, and the results have been equally strong: Significant increases in employee retention; immediate declines in employee absences due to illness an injury; a dramatic decline in personnel complaints; and, a more easily preserved culture of higher standards and performance.

The lesson here is not that we can simply adapt to changes in our available workforce. The lesson I learned is that we can discover the learning of organizations that changed their industries and adapt them to our mission for new forms of success.

This article was originally published at http://www.careersingovernment.com